Previously, this position statement was entitled ‘General Principles of Feline Welfare’; however, the changes in the understanding of ‘welfare’ vs ‘well-being’ over the past decade necessitated an update to the statement. ‘Well-being concepts’ has been proposed as a term that encompasses welfare, well-being, quality of life, and happiness,1 and is adopted in this statement.

What are well-being concepts?

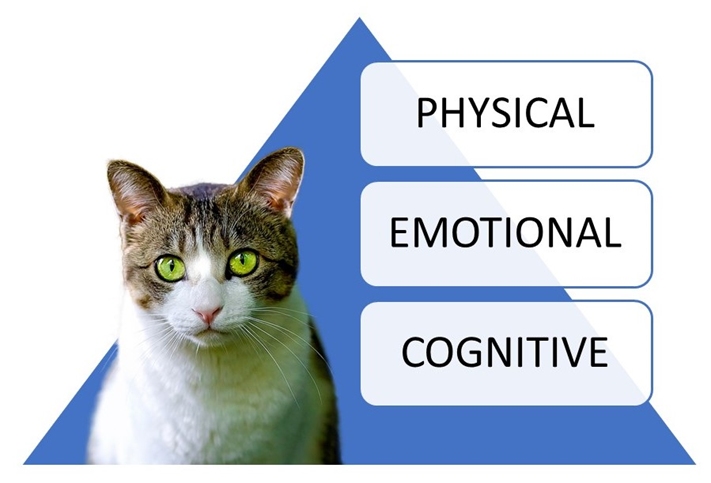

The FelineVMA (formerly AAFP) supports positive well-being concepts in cats. These concepts are internal states that are specific and unique to each individual cat, and, as veterinarians, we can only serve as the cat’s proxy. Our professional responsibility is to understand the physical, emotional, and cognitive (mental) needs of each feline patient in our care because all three components (the ‘health triad’) are inextricably linked and equally important (Figure 1).

The cat as a ‘non-obligate’ social creature

Remembering that the domestic cat (Felis silvetris catus) evolved from an asocial species3 is essential to understanding feline motivations. Our feline patients are non-obligate social creatures – an entity unto themselves – and have retained their protective mechanisms for

survival from their ancestors. Wide variability occurs in each feline patient’s sociability with other cats and other species, including humans, and this is based on an individual’s genetics, life experiences and sense of safety ‘in the moment.’ Individual experiences during the sensitive period of development (usually from 2 to 9 weeks of age4) are especially critical. Negative experiences at this stage can create a foundation for a lifetime of fear and stress in the adult cat.5 Feline sociability is highly variable; therefore, not all cats benefit from the company of another cat.

Quality of life: seeking the positive, avoiding the negative

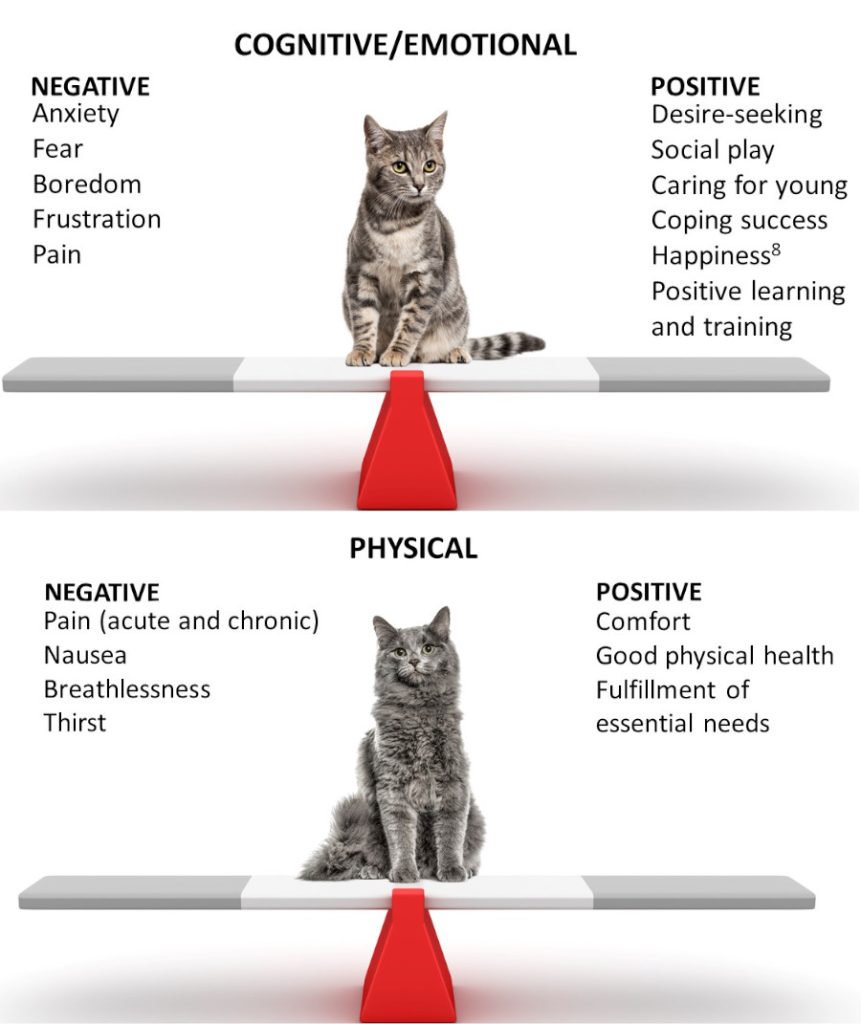

Cats are sentient beings and experience both positive and negative emotions, with an ability to seek the positive and avoid the negative.6 Promoting positive emotions – including normal species-specific behaviors – and minimizing negative emotions, such as fear, frustration, and pain, enhance feline well-being.6 Both positive and negative emotional states are important. Cognitive health is defined as being able to clearly think, learn and remember.7 The goal should be that positive cognitive, emotional, and physical elements outweigh the negative (Figure 2).

As sentient beings, cats live in the moment, without knowledge of the future. Quality of life can be described as ‘an individual’s satisfaction with its physical and psychological health, its physical and social environment and its ability to interact with that environment.’9 In turn, health may be described as ‘the state of being free from illness or injury,’ and satisfaction as ‘the fulfillment of one’s individual needs or (state of) positive mood.’9 Companion cats’ experiences are not always positive in the home or in the practice. An individual cat may not benefit from the company of another cat (eg, territorial conflict, intercat tension). There is mounting evidence to suggest that a negative experience during a veterinary visit, including a kitten’s first examination, may impact long-term patient well-being (ie, create fear and distress) at home and at future visits.5,10 This thus demonstrates the importance of becoming a Cat Friendly Practice, as well as utilizing and incorporating cat-friendly handling and interactions, and a Cat Friendly environment and veterinary experience (available at: catvets.com/cfp).

Creating an environment for positive well-being

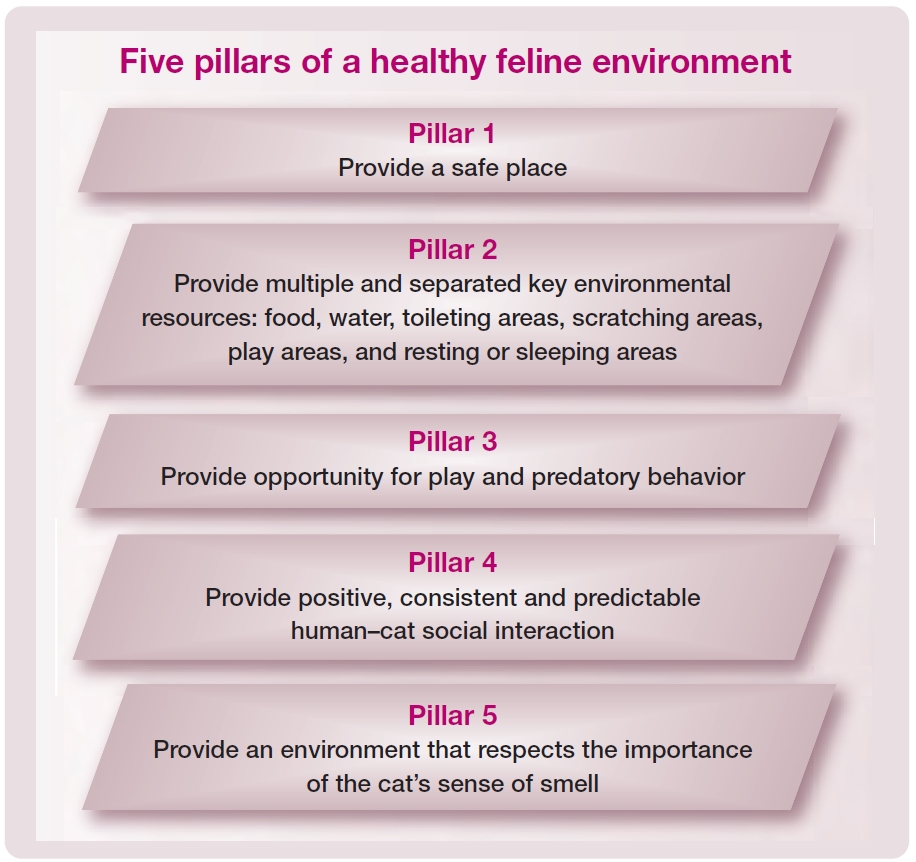

Each cat must feel safe to find pleasure and comfort in their environment, the home, the outdoors, and the veterinary practice. The AAFP and ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines’ five pillars describe the essential needs of the cat’s environment (Figure 3).11 Essential needs should not be confused with feline enrichment.11

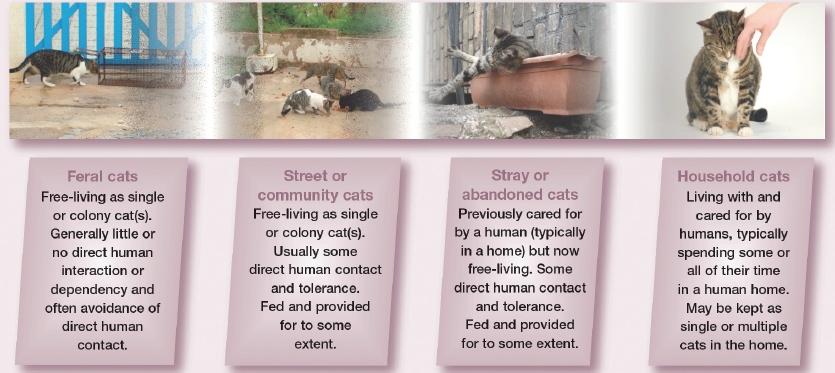

The Guidelines provide a full explanation of each pillar (available at: catvets.com/environmental-guidelines). Fulfilling the components of the FelineVMA’s ‘five pillars’ concept is essential for the overall well-being of every cat, regardless of their behavior and lifestyle (Figure 4).

Addressing negative well-being

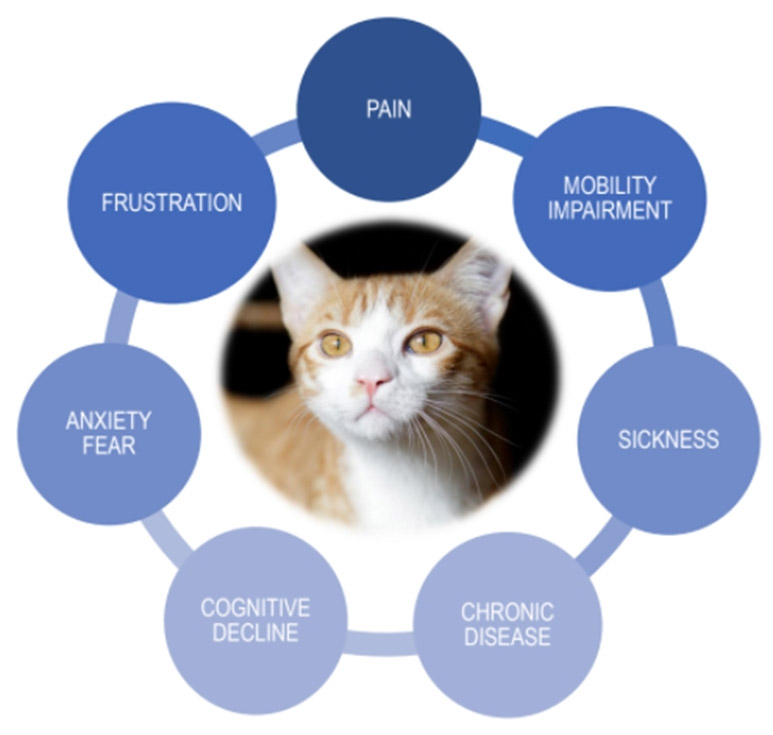

All factors contributing to negative well-being are deserving of veterinary attention (Figure 5). One of these factors is pain, which has sensory and affective components and is always unpleasant. Pain is commonly under-recognized and undertreated in our feline patients, both in the practice and at home. Providing effective acute and chronic pain management is an important way we can contribute to the positive well-being of cats. Three essential points to recognize in order to minimize negative well-being in the veterinary practice are:

- Interactions with, and physical handling of, cats must be performed in such a way as to minimize distress, fear/anxiety, and pain.

- All diagnostic, medical, and surgical procedures must be performed in such a way as to minimize distress, fear/anxiety, and pain. If it is anticipated that a diagnostic, medical, or surgical procedure will cause pain, then effective pain management should be initiated prior to the procedure and continued for an appropriate duration, based on pain assessment (see ‘Recommended reading’).

- It must be remembered that many cats have chronic underlying pain (eg, osteoarthritis, periodontal disease), which exacerbates pain related to handling and procedures.

Supporting well-being through all life stages

Each veterinarian and veterinary team member has a professional duty to understand and promote the physical, emotional, and cognitive needs of each cat at all life stages.12 Educating the owner to maximize positive and minimize negative experiences and emotions is essential to ensure the cat’s well-being.

References:

- McMillan FD. The problems with well-being terminology. In: Yeates JW (ed). Mental health and well-being in animals. 2nd ed. Wallingford: CABI, 2019.

- Heath S. Environment and feline health: at home and in the clinic. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2020; 50: 663–693.

- Driscoll CA, Macdonald DW, O’Brien SJ. From wild animals to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106 Suppl 1: 9971–9978.

- Bradshaw J. Normal feline behaviour: … and why problem behaviours develop. J Feline Med Surg 2018; 20: 411–421.

- Lloyd JKF. Minimizing stress for patients in the veterinary hospital: why it is important and what can be done about it. Vet Sci 2017; 4. DOI: 10.3390/vetsci4020022.

- Panksepp J. Affective neuroscience: the foundations of human and animal emotions. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- National Institute of Health. Cognitive health and older adults. National Institute of Health: National Institute on Aging. nia.nih.gov/ health/cognitive-health-and-older-adults (2020, accessed September 27, 2021).

- Quimby J, Gowland S, Carney HC, et al. 2021 AAHA/AAFP Feline Life Stage Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2021; 23: 211–233.

- Belshaw Z, Asher L, Harvey ND, et al. Quality of life assessment in domestic dogs: an evidence-based rapid review. Vet J 2015; 206: 203–212.

- Overall KL. Evidence-based paradigm shifts in veterinary behavioral medicine. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2019; 254: 798–807.

- Ellis SLH, Rodan I, Carney HC, et al. AAFP and ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 219–230.

- Sparkes AH, Bessant C, Cope K, et al. ISFM Guidelines on Population Management and Welfare of Unowned Domestic Cats (Felis catus). J Feline Med Surg 2013; 15: 811–817.

This Position Statement has been updated from: General Principles of Feline Welfare.

Download Position Statement© Feline Veterinary Medical Association, 2025